The International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots (MM&P) has recently developed an engaging research in conjunction with Dalhousie University (Canada) titled SPOTLIGHT ON SAFETY: WHY ACCIDENTS ARE OFTEN NOT ACCIDENTAL. It discusses various cases when the crew breaches onboard Safety Management System procedures deliberately and reasons which make them break the rules.

The report states that many maritime accidents would never have happened if only officers hadn’t been discouraged from reporting vessels’ deficiencies; commercial interest hadn’t dominated minds of decision makers and inspectors hadn’t averted their eyes from obvious defects being sometimes under pressure themselves.

“Ships make money at sea!”

Authors imply that commercial pressure in all spheres of the shipping industry takes its toll on safety. Coming right from the top, it focuses on ship officers and crews who have to ensure timely arrivals and departures, smooth cargo loading and operation of the vessel, fuel economy and environmental protection.

Seafarers are urged to keep their vessels going. Many engineers perform onboard repairs of equipment that actually requires attention of a special maintenance technician from the manufacturer. Meanwhile, bridge officers are able to make a passage receiving next destination as a text on a cell-phone because there is no other means of communication or battling with constant black outs.

The report also points that commercial pressure is put on vessel inspectors; which jeopardize safety even further. Flag States compete with each other for shipowners, so might encourage their associated staff to be lenient with their customers, “close their eyes” for some deficiencies in order to avoid delays.

El Faro Accident

Authors of the report feature SS El Faro accident as a prominent example of commercial pressure on the officers that led to tragic consequences when met with safety inspection negligence and some really bad luck.

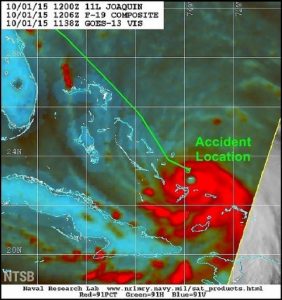

American cargo vessel El Faro sank on the 1st of October 2015 near Bahamas almost in the eye of Hurricane Joaquin claiming lives of all 33 crewmembers. El Faro was on her way from Jacksonville (US) to San Juan (Puerto Rico) when she rammed headlong into Hurricane Joaquin which was quickly deteriorating from Category 2 tropical storm to Cat 4 hurricane with a 255 km/h wind (155m/h) and killing waves. A VDR evidence points that is was the Master’s decision to make a passage right through the storm.

Contributors to the Safety Report contradict findings of the NTSB (National Transport Safety Board) that put the blame solely on the Master’s mistake and bad weather. They insist that Captain must have been under a considerable pressure from the management to keep the course; and as investigation has shown was provided with out-dated weather report.

However, the sinking wasn’t the result of the harsh weather only. Seawater started flooding a cargo hold through a partially enclosed deck and open hatches several hours before the disaster (El Faro disaster brought about regulation about hatch indicators). The cargo hold filled gradually with seawater, so cars there broke free and might have damages the main fire pipe which was fatal for the vessel. The Master ordered to leave the sinking ship, but El Faro had only the open uncovered lifeboats, useless in that weather. The situation with hatches and lifeboats was acknowledged as a tragic oversight of USCG (US Coast Guard) as they had been understaffed for the inspection.

Sack a Whistleblower

Among other distressing findings of the report is a general tendency of operators to discourage theirs crews from producing CARs (Corrective Action Reports) or complain about safety matters in any other way.

“Maritime companies do not like having a documented trail of failures to comply with the ISM Code or other regulatory requirements. Multiple infractions may make them susceptible to increased scrutiny by Port State Control or other regulatory agencies. This could jeopardize schedules, increase repair costs at an inconvenient time, or leave a trail for a charge of negligence and liability in the event of an accident.”

Therefore, management might develop a habit of ostracizing personnel who produce safety reports which results in crew withholding information about deficiencies in a fear of retaliation.

In fact, there had been quickly hushed maintenance requests before the Deepwater Horizon disaster, but there are also happy endings. The report describes former Noble Drilling’s Captain Jeff Hagopian’s case. He used to be the OIM of Noble Danny Adkins rig from 2010 till 2015 with immaculate performance evaluations when suddenly was sacked after filing a report on safety violation.

He reported to the Noble’s alternate DPA the false “red entry” in the log book claiming that the crew had performed the quarterly launching and maneuvering of lifeboat; and an attempt to mislead USCG during the inspection. However, he didn’t know that Noble Drilling Company has just entered its criminal probation after pleading guilty to safety and oil pollution violations connected with Noble Discoverer, so it was management direct order to distract inspectors’ attention on Noble Danny Adkins.

After his abrupt termination Captain Jeff Hagopian has filed a lawsuit against Noble Drilling and won the case.

Duck and Cover

Another issue addressed by the report is fleeing from responsibility. SMS code requires all safety deficiencies to be communicated to DPA (Designated Person Ashore) whose job it is to bring onboard problems to the attention of the management. Research responders confirm, though, that in reality such communication is often dissuaded. This way management is able stay clear of any negligence accusations on the grounds that they didn’t know. As a result, seafarers take the whole responsibility in case of onboard accidents.

The most famous such case is, perhaps, the Prestige oil spill. MV Prestige was a 26-year old single-hulled oil tanker, operated by Greek company. She was carrying 77 000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil and was caught by winter storm off the Spanish Coast in November 2002. The starboard cracked opening a 15 meters (50 ft) hole; the tanker began leaking oil. Captain Apostolos Mangouras asked for help from Spanish authorities. The Filipino crew was evacuated, but he’s never got his way about taking Prestige to dock and confined leakage.

The damage tanker was towed from the Spanish north-west coast, but wasn’t welcomed in French waters either. So was dragged towards Portugal instead. They didn’t allow MV Prestige to dock either and send the navy ships to prevent the oil leaking tanker approach. As a result, it split in half after 6 days wandering spilling 50 000 tonnes of oil and causing the worst oil pollution in the history of Spain, France and Portugal. Contamination was considered even higher compared to Exxon Valdez disaster which we described in our Tanker article because of warmer sea water.

Investigation has shown that Prestige hull failure had been predicted earlier. Her 2 sister ships were subjected to extensive inspections and scrapped due to metal fatigue. It was Prestige’s turn next. Moreover, it is known that her previous Captain Esfraitos Kostazos complained to the owners about numerous deficiencies, was retaliated and resigned in protest.

Spanish authorities have been criticized heavily for not bringing MV Prestige to port in time, but neither officials from three counties, nor shipowners or inspectors who have allowed damaged vessel into the sea were accused of the disaster. The only legal consequence was the arrest of Captain Apostolos Mangouras for disobedience to Spanish authorities when he insisted on Prestige being brought to the port while navy officers required him to restart engines and leave the Spanish waters. Captain Mangouras was sentenced to 9 months in prison. The term suspended because of his advanced age (he was 78 years old at a time).

The final cost of a clean up after the Prestige oil spill measured 398 million euro ($494 million).