The term ‘offshore energy’ has long lost its petrolic smell. Now it’s all about alternative energy inputs. Technological development facilitates expansion of the offshore wind industry; while the need for the ecological and cost-efficient electrical energy is pending as ever.

According to World Forum Offshore Wind, 2018 was the record breaking for the industry as almost 5GW offshore capacity was added during the year bringing the total world OWF capacity to 22 GW; and they are not going to stop. The organization has proclaimed a mission “500 by 50” aiming at installation of offshore facilities able to produce 500 GW of energy worldwide by 2050.

So, what do we know about these modern offshore wind farms? How so many offshore foundations will co-exist with shipping industry? Will they just become great annoyance for maritime professionals or create new jobs for seafarers by opening new market of offshore vacancies remains to be seen.

Fast Facts about Offshore Wind Farms:

- There are 5 556 offshore wind turbines in the world.

-

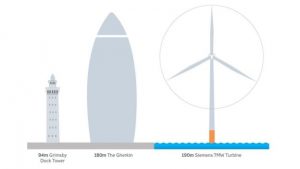

Image Credits to BBC The world’s largest offshore turbine started operation on February the 15th The 190m (623 f) high turbine is the first of 174 windmills that will be built at the Hornsea One development located 120km (75 miles) off the Yorkshire coast. When completed in 2020 it will produce electricity for more than million homes.

- Majority of wind farms are situated in Germany, Denmark, UK, Spain as well as other European countries.

- However, China, Taiwan, South Korea and the USA have joined an active building program for offshore wind energy.

- Offshore wind farm is 90% more expensive than fossil fuel combustion and 50% more expensive than nuclear power, but each turbine works up to 40 years and produces no waste.

- Offshore wind installations produce 50% more energy than onshore farms due to higher wind speeds at sea.

- Sociological researches have demonstrated that choosing between 2 projects a city community is more likely to favor an offshore wind farm because of aesthetical reasons (‘out of sight out of mind’ principle).

The world’s largest and most technologically advanced offshore Installation vessel will be delivered later this year. DP3 DEME Orion will be 216.5 meters (710.3 feet) long equipped with crane possessing lifting capacity of 3,000 tones. The crane will be able to lift loads at 170 meters (558 feet).

The world’s largest and most technologically advanced offshore Installation vessel will be delivered later this year. DP3 DEME Orion will be 216.5 meters (710.3 feet) long equipped with crane possessing lifting capacity of 3,000 tones. The crane will be able to lift loads at 170 meters (558 feet).

Opportunities of the Offshore Wind Industry

There has been an exponential growth in the industry of offshore wind farms during the last decade despite some technological and economical difficulties in projects development. Today with the arrival of bigger and advanced offshore turbines investors are even more willing to participate in the ventures. Moreover, governments subsidize or provide privileges to such projects in many countries.

Even if one puts aside optimistic mission of WFO, there is a fresh report from Navigant Research stating that over 69GW of new offshore wind capacity will be installed between 2018 and 2027 and 100 GW is expected to be installed by 2030.

Such development pace means that Offshore Wind Industry will engulf a lot of manpower to achieve its goals which a great news to professionals worldwide. Experts believe that wind energy will employ 479,000 people in the EU by 2030 of which 294,000 – 61 % of the total – will be in offshore wind energy. On a global scale, the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) expects that by 2030 the wind industry will employ between 800,000 and 3 million people depending on the development scenario considered. For instance, each offshore installation vessel that is involved in the construction of an offshore wind farm accommodates approximately 130 crewmembers; and there are several such vessels on every project. Then, there are technicians who construct and maintain turbines. At present it is a growing job market with multitude of opportunities.

Shipping vs. Offshore Wind Farms

In spite of inviting career prospects, offshore wind industry won’t be everyone’s choice. Furthermore, it is likely to become a source of perpetual irritation for professional seafarers as OWFs congest already overcrowded maritime space.

There haven’t been many accidents connected with OWF yet. The most well- known is offshore support vessel OMS Pollux colliding with a turbine off the England coast in August 2014. None of the 18 crew members was injured, but the vessel leaked fuel.

However, experts admit that the small percentage of accidents is only attributed to the current moderate number of offshore wind farms. A team of researches provided a calculation of ship-turbine collision in the Wadden Sea where the density of shipping lines and wind farms is maximum today. They got an inevitable collision every 10 years. Scientists also admitted that they have not included a human error factor in their calculations which is likely to increase the chances of an accident.

Nobody would agree even to such probability. Moreover, in case with a tanker or passenger vessel, the consequences of a single accident might be disastrous. Therefore, before any OWF project is approved and licensed the Navigational Risk Assessment (NRA) process takes place together with Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). However, only the Netherlands do NRA on the governmental level. The rest leave risk assessment for the project developers.

The NRA often takes the form of the IMO’s Formal Safety Assessment (FSA) and defines co-existence of an offshore wind farm with local maritime industry. The recent research showed an interesting result. Only 16% of seafarers are aware of Navigational Risk Assessments for OWF and among these 16% only half agree with their results.

Meanwhile, each NRA is a lucid document containing AIS maps, risk scenarios and engaging calculations of ship-turbine and ship-to-ship collisions in the most crowded navigational areas. For instance, for Omø Syd Wind Farm in Denmark the presence of wind farm has brought the probability of grounding incidents to 1/40 years and ship-to-ship collision to 1/ 18 years.

Protective Measures

There is an open discussion how to ensure navigational safety in the areas of offshore wind farms. Some seafarers point that the problem is overestimated. Farms have a clear light indication at night and are built in regulated rows, so there is no difficulty is plotting the route. But all calculations show that collision will happen from time to time. If the fleet of service tug boats is employed to rescue drifted vessels, it’s possible to reduce collision probability to 1/100 years in some areas, but there is still the human error factor.

To protect both turbines and vessels some engineers came up with ideas of protective jackets made of rubber or steel. Other design ideas presupposed rubber fender, aluminum foam pads and inflatable tube like structures that were called to take the impact of a ship collision. Some experts like Louis Coulomb, a Dutch structural engineer who specializes in wind turbine development, take an opposite view and state that such protective armor would likely weigh up to 130 tonnes and cost about a third of foundation and turbine itself. So, it’s more reasonable to save costs on protective measures and let a turbine fall causing no or little damage to the vessel in case of a collision.

However, this method is unsuitable for the last generation of OWFs built far off the coast where the sea is deep and rough. These turbines are bigger (190 m high) and supported by underwater tripods instead of fragile monopods in shallow waters. If a vessel were to hit one of the diagonal struts of a tripod at just the right angle, it could tear a sizeable hole even if the vessel is reinforced with a double hull. Groups of engineers are developing the decision for this issue at present.

The exciting fact about OWF industry is that we contemplate its booming growth. These are still early days, all stakeholders still learn. For instance, the global wind community discovered a couple of months ago that there are no international cyclones and earthquake standards for wind turbines. The need for such document became apparent when Asian countries started developing OWF projects; e.g. Guangdong region in China which will receive 500 offshore wind turbines in the next couple of years was hit by 18 typhoons during the 2018 season. Now DNV GL is calling for industry stakeholders to take part in the development of the standard.

This example demonstrates that the industry is still very young, but there are much resources and initiative behind it. Therefore, there are a lot of opportunities for the offshore wind industry itself and auxiliary services like offshore installation and supply for further development and growth.